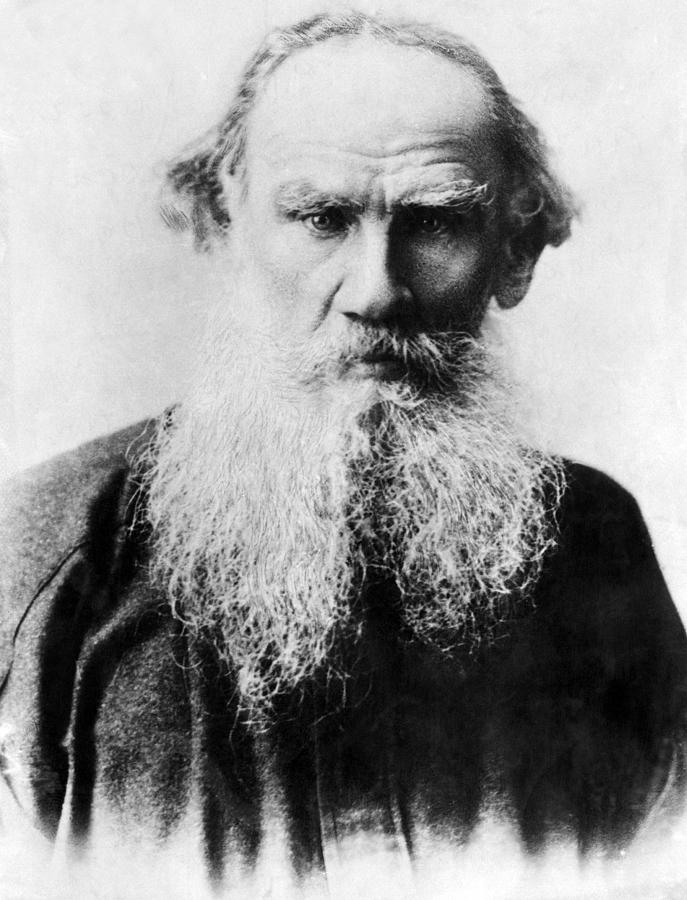

Like all his later works, whether treatise or play or novel or parable, this volume on art shows Tolstc~i in his character of lay prophet, with all its powers and all its weaknesses. LEO TOLSTOI'S recent volume on Art closes significantly the series of his arraignments of what we have been pleased to call civilisation. Gospels of Anarchy, and other contemporary studies. This concept was gradually elaborated in the 970s and 1980s, but only in the 1990s did it become more fully developed and widely discussed.Lee, V. This article discusses his concept and explains some of its more complex aspects, before addressing the emergence of a very similar concept within Anglo-American aesthetics. One interpretation construes the expressiveness of works of art in terms of the expression of a fictitious subject, the ‘work’s persona’, conceived by Elzenberg in the 1950s and 1960s.

But the widespread tendency to conceptualize the emotional content of art in terms of the expression of a certain subject (most often the artist) still requires some explanation – interpretation, rather than negation. At the same time, these authors demanded that the term ‘expression’ be expunged from the language of aesthetics. Thanks to Bouwsma and Beardsley, this concept – of expressiveness as a quality – became common in Anglo-American aesthetics from the 1950s onwards. A way out of this predicament – one which the Polish aesthetician Henryk Elzenberg (1887–1967) was among the first to propose – was suggested by the idea that physical, sensory objects can themselves possess emotional qualities. Consequently, formalism declared it to be irrelevant to a work’s value.

This content thus appeared to be external to the work itself.

Classic expression theory identified the emotional content of works of art with the feelings of the artists and the recipients.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)